What are the odds of getting hired? Jobs, chess, and polynomials

If you are a new graduate like me, there is a good chance that you are having trouble finding a place to start your career. There are quite a few of us in the market right now, and due to the pandemic, fewer available jobs than normal. Among the endless applications, resume revisions, and LinkedIn searches, quite a few of us have begun to wonder: what are our odds of getting hired right now?

An overview

I asked myself this question recently, and having taken a combinatorics course in my undergrad, could not help but explore it mathematically. Before moving on, I do want to say that this will not be a proper statistical analysis of the hiring process during lockdown. It will, instead, be an exercise in solving an interesting combinatorial problem, and developing a useful model of the job market.

First, as a refresher, we may estimate the probability of an event \(E\) through a sequence of fair trials by using the formula

\[P(E) \approx \frac{N(E)}{N(T)}\]Where \(P(E)\) is the probability of \(E\), \(N(E)\) is the number of times that the event occurred in the trials, and \(N(T)\) is the total number of trials.

In our question, we want to know what the odds of getting hired are. Our event is you, or me, or any single individual getting hired for any job. The trials are ways, after the dust has settled, that companies have hired people.

Initially, this problem might seem simple. Let’s introduce John, who is applying for a job as a software engineer at a large tech firm. John is not the only person interested in this job, and is competing with 49 other people for this one position. If we ignored interview performance, personality, and other interfering factors, we could easily calculated John’s probability of being hired to be \(\frac{1}{50}\), or \(0.02\). However, the world of job hunting is not this simple. John likely applied to other jobs as well, to increase his own odds of being hired, as did those 49 other people. Further, John may be competing with some of the same people for those other jobs, meaning that if they got hired for those other jobs, his odds with this first job would actually increase, since they would no longer be in the pool of applicants.

As it turns out, this problem is much, much more interesting. The event \(H\) is of John being hired. We will use two symbols, \(N_h\), and \(N_d\) to represent the number of ways in which John has been hired, and the total number of ways that jobs may be distributed, respectively. Then we arrive at the following formula:

\[P(H) \approx \frac{N_h}{N_d}\]We need to figure out how to develop a model which can tell us what \(N_h\) and \(N_d\) are. We arrive at a combinatorial question: how can we count the ways that jobs can be distributed? To answer that, we first need to talk about chess.

Counting rooks

Let’s start by asking a related, but different question: how many ways can you place non-attacking rooks on a chess board?

In chess, a rook ♖ may attack pieces above, below, and to its sides. For a rook to be non-attacking, these areas must be clear of any other pieces.

Initially, this is a simple problem. If we place a rook, we eliminate the ability for us to place a rook in that row or column. If we iteratively choose rooks from free spaces left on the board, we notice a pattern. The first rook eliminates 15 spaces, the next rook 13 (since two were already eliminated by rook 1), the next 11, and so on. If we describe the number of ways to place the \(n^{th}\) rook, we get the sequence, \(r_n = 64, 49, 36, \ldots\), described by \((8 - (n - 1))^2\). Then, our desired function, the total number of ways to place \(n\) rooks, \(R(n)\) is

\[\begin{align*} R(n) &= r_n \cdot r_{n - 1} \cdot r_{n - 2} \cdot (\ldots) \cdot r_1 \\ &= \prod_{j = 1}^{n} r_j \\ &= \prod_{j = 1}^{n} (8 - (j - 1))^2 \end{align*}\]Further reductions are left as an exercise to the reader.

Importantly here, we notice the recursive nature of solving this problem. While we could view each decision to make as a function of the previous decision, we could also notice that each rook placement essentially leaves us with a smaller, but still square, board. For each rook we place, we are simply choosing from progressively smaller boards. Our problem is recursive: each successive rook placement can be seen as its own small version of the larger problem.

This so far has been a relatively simple problem. However, one might start thinking about how to generalize to non-standard boards. Before then, though, let’s get back to John, who is still just trying to find a job.

Getting hired is a game of chess

As a reminder, we are trying to count the number of permutations of hirings that allow John to be hired, and the number of permutations of hirings in general. We’ll tackle that second part first.

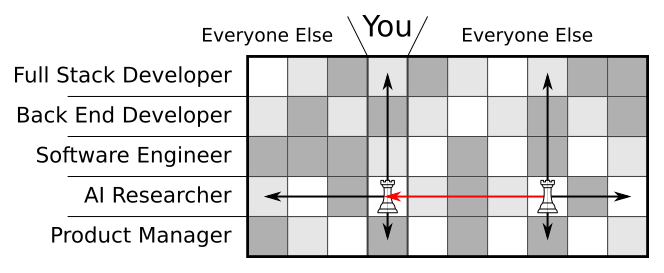

Let’s first examine a much smaller and simpler version of this problem. Let’s say that John, being a generalized software engineer, is applying for three different positions: front end developer, AI developer, and compiler engineer. Unfortunately for John, he is not alone. Faye, Elliott, Lee, and Maria are also looking for jobs, and have also applied to some of these jobs.

-

Faye has applied to the front end developer position, as well as a full stack position.

-

Elliott has applied to the AI developer and compiler engineer positions.

-

Lee has applied to just the AI developer position.

-

Maria applied to the front end and AI developer positions, and the same full stack position as Faye.

Let’s assume that there are no applicants for any of these three positions, or the additional full stack position. How can we even begin to count the ways that these jobs may be distributed? We will make a chart, relating positions and people. We darken out any position that a person did not apply for.

What happens when a person is hired for a position? Well, not only do they celebrate with take out pizza, a glass of champagne, and a few too many Oreo cookies, but they also remove themselves and the job from the market. For example, if Elliott were to be hired as an AI developer, we would oberve the following change to the chart.

Hmm, this pattern seems familiar. Might we have seen something similar before?

As it turns out, match people with jobs reduces easily to the same problem of placing rooks on a chessboard! As such, we can rephrase our question of “how many ways can jobs be distributed” into something involving the placement of rooks on this board. We will call this chessboard \(B\).

In a perfect world, we would assume that everyone would coordinate to maximize the number of hirings. In this case, we would ask for the number of ways to place the maximum possible number of rooks on this board. However, it is not a perfect world - sometimes jobs close, people pull themselves off the market, and competing jobs poach each others’ choices. As such, we instead need to count every possible hiring permutation - that is, counting every case which could even be considered remotely possible, including a case where nobody is hired at all. So, our question becomes “how many ways can we place any number of rooks on this board?”.

However, now we need to find a way to deal with these “darkened” spaces.

Polynomials

When dealing with permutations of various indistinct items (rooks), a common combinatorial tool is to encode the problem in a polynomial, called a generating function. That is, we change from a question of “how many \(n\) are there?” to “what is the coefficient of \(x^n\) in the polynomial \(P(x)\)?”. In this case, we will introduce a function \(R(B, x)\) which yields the “rook polynomial” for our board, \(B\).

So, what do we get from using polynomials to encode our problem? The answer lies in how polynomials can be composed and combined with each other. We will find several important uses of polynomials as we break down \(B\) into something countable.

Changing the board

Initially, counting rooks on this board is difficult, and tedious to do by hand. It is better to break the problem into smaller parts, which are more feasibly counted.

A nice feature of rook placements is that they only interact with the squares directly above and below them. Knowing this, we can transform the board, as long as we don’t alter the alignment of columns and rows. We can then swap any two rows or columns of the board as many times as we need, and it will not affect our count of rook placements. We have used this property here to transform \(B\) into a board with two isolated corners of valid spaces.

What did we get from doing this? Well, there are now two nearly non-interacting sub-boards By non-interacting, I mean that a rook placement on either of these smaller boards has no effect on rook placements on the other board. We will call these sub-boards \(B_1\) and \(B_2\).

It is much easier to count rooks on these smaller boards, and the non-interaction will be key in our ability to use these simpler counts for the larger board. For now, we will not worry about the two squares lying outside of these two subboards, and will simply use the larger board \(B^{\,\prime}\) for many of the counts here.

Counting coefficients

Let’s find the rook polynomials \(R(B_1, x)\) and \(R(B_2, x)\). As stated above, this will be done by encoding the number of ways to place \(n\) rooks on the board as the coefficient of \(x^n\).

On board \(B_1\), we have a trivial 2x2 square. We can easily count that there are \(4\) ways to place one rook, and \(2\) ways to place two rooks. We also must count the single way that there is to place no rooks. Note that there are no ways of placing three or more rooks, so these coefficients in the polynomial will be \(0\), and are not written. We have now arrived at our polynomial:

\[R(B_1, x) = 1 + 4x + 2x^2\]We can similarly easily perform the counts for \(B_2\), and arrive at the second rook polynomial:

\[R(B_2, x) = 1 + 5x + 4x^2\]How are these useful in counting the larger board \(B^{\,\prime}\) and its equivalent board \(B\)? The non-interaction is key here. Think about a single count of rooks, like \(2\). When placing rooks on the larger board, how would rook placements on these sub-boards contribute to that count? In this case, there could be \(0\) rooks from \(B_1\) and \(2\) rooks from \(B_2\), \(1\) rook from \(B_1\) and \(1\) rook from \(B_2\), or \(2\) rooks from \(B_1\) and \(0\) rooks from \(B_2\). Then, the coefficient for \(x^2\) in the polynomial for the larger board, \(B^{\,\prime}\), is the sum of the number of ways to place those two choices. But this is just how we calculate coefficients when we multiply two polynomials. Thus, we can say that

\[\begin{align*} R(B^{\,\prime}, x) &= R(B_1, x) \cdot R(B_2, x) \\ &= 1 + 9x + 26x^2 + 26x^3 + 8x^4 \end{align*}\]We now have a way to derive our larger polynomial from the two smaller ones! This is, of course, still ignoring those two outlying white squares. How about we deal with those now?

Eliminating outlying squares

We will eliminate those outlying squares by investingating two disjoint cases: when a rook is placed on the square and when a rook is not placed on that square. First, we will eliminate the top right outlying square in \(B\), highlighted below.

Let’s construct two boards, \(B^\circ\) and \(B^{\bullet}\) which represent \(B\) with and without a rook placed on the square, respectively. If the square does not have a rook, then we simply may darken it out. If the square does contain a rook, then we must darken both it, and its row and column, since after placing a rook there, all spaces in the row and column are now not valid for rook placement.

Again, we will ask how we can construct the rook polynomial for \(B\) using the polynomials for these altered boards. Let’s just ask what these respective polynomials represent, firstly. \(R(B^\circ, x)\) tells us how many ways we can place a number of rooks, with none being on the indicated square. One would think that \(R(B^\bullet, x)\) would conversely count the number of rooks with one on the indicated square, but this is not so. It does not encode how many ways you can place rooks after the initial rook has been placed, but it does not count that initial rook. However, \(x R(B^\bullet, x)\) does, since it raises the number of rooks encoded in every coefficient by \(1\). But now we are done, since we have counted all of the rooks in the two disjoint cases which together make up all of the ways to populate rooks in \(B\). We now have a complete formula for \(R(B, x)\) in terms of these two altered boards:

\[R(B, x) = R(B^\circ, x) + R(B^\bullet, x)\]Putting it all together

We are now equipped with all of the tools that we need to construct the polynomial \(R(B, x)\) and find the number of ways that we can distribute jobs among these applicants.

So, we have finally reached our desired rook polynomial, \(R(B, x)\). Now we need to return to our original problem statement - counting ways to distribute jobs.

Distributing jobs

We now return to our original question: what are the values of \(N_h\) the number of job distributions in which John is hired, and \(N_d\) the number of ways to distribute jobs among these applicants? Our polynomial has all the information that we need. Since each coefficient of \(x^n\) in the polynomial represents the number of unique ways to distribute \(n\) jobs, and each of these counts is unique among each other, we can find the total number of ways to distribute jobs by summing all of the coefficients in the polynomial. Formally, we write

\[\begin{align*} R(B, x) &= \sum_{n \geq 0} a_n x^n, \\ N_d &= \sum_{n \geq 0} a_n, \\ N_d &= 1 + 11 + 36 + 39 + 11 = 98 \end{align*}\]Now, all that is left is to calculate \(N_h\).

Getting John hired

Fortunately, we are well equipped with the tools needed for this last task. Actually, the way that we will calculate \(N_h\) is similar to a technique that we used earlier to simplify our board. We will place a rook on each of the open spaces in the row representing John, and then count the number of ways to place any more rooks on each of those boards. The sum of all these counts will be \(N_h\).

We are now able to see the rook polynomials for these boards, finding them to be \(1 + 6x + 9x^2 + 2x^3\), \(1 + 7x + 12x^2 + 4x^3\), and \(1 + 5x + 6x^2 + 2x^3\) respectively. Summing up the coefficients, we calculate \(N_h\):

\[\begin{align*} N_h &= 1 + 6 + 9 + 2 \\ &+ 1 + 7 + 12 + 4 \\ &+ 1 + 5 + 6 + 2 = 56 \end{align*}\]The answer (for John)

Now the we have found the values of \(N_h\) and \(N_d\), we return to our original formula for \(P(H)\), the probability of John being hired in this job market.

\[P(H) \approx \frac{56}{98} \approx 57 \%\]The answer (for the rest of us)

What we have created here is a model of the job market. It is limited in the fact that it cannot assign weights to certain people to be favored in one job over another, and it counts all scenarios equally. However, it has been a fun and useful exercise in using combinatorics to model discrete problems, and in thinking a little outside of the box, mathematically.

Can you apply this model to yourself and the real world job market? No, as you have neither the information nor the computing ability to be able to build a board out of every job and person competing with you. Still, it is through abstract thinking like that applied here that we can develop more complex and precise models of the real world.

Thank you for reading.

I hope that, if anything, this approach has left you with some curiosity for other combinatorial problems and their solutions. If you are interested further, I would suggest picking up Alan Tucker’s Applied Combinatorics, the textbook used in my university combinatorics course. There are quite a few interesting problems, and unexpected connections to other areas of mathematics.